Walt Disney’s Three Little Pigs was an instant legend among animators, then just starting to develop their craft. It also was an instant legend among film studios, who saw that for once, a cartoon could be a bigger draw than the main feature.

Naturally, rival Warner Bros had to get into the action, with three different cartoon takes on the three little pigs.

And equally naturally, their first take was a direct slam and parody of their great rival.

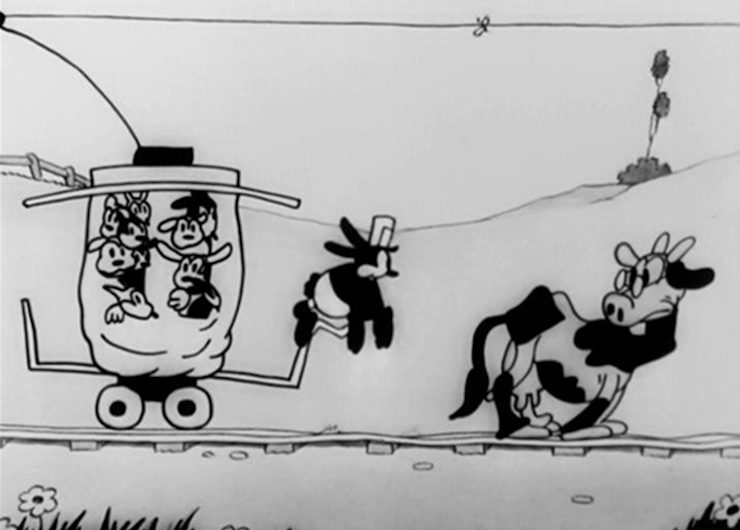

Animation director Friz Freleng (1905-1995)—born Isadore Freleng, and occasionally credited as I. Freleng —had actually worked for Walt Disney before Disney was even Disney, in the very early Laugh-o-Gram days. Enjoying the work, he followed Walt Disney to California in 1923 and worked on many of the very earliest Disney cartoons, including those focused on Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. In 1929, he left Disney for reasons that remain somewhat disputed, though his own fabled temper may have made it difficult for him to work for Walt Disney.

At his next employer, Warner Bros, Freleng helped found Merrie Melodies, the cartoon line that, unlike WB’s other cartoon group, Looney Tunes, did not need to feature Warner Bros music, giving animators on that line a touch more flexibility. Freleng worked to master the syncopation of image and music. The Merrie Melodies cartoons also featured something else that Looney Tunes did not: color. Not, at that time, necessarily the best color—Walt Disney had seized exclusive use of the brilliant Technicolor process, initially leaving Merrie Melodies stuck with a rather inferior if decidedly cheaper color process, Cinecolor. But Merrie Melodies had something Disney did not: a voice actor called Mel Blanc, then contracted to Warner Bros radio station. Freleng and Blanc together created a little character called Porky Pig, and then, Freleng headed off to MGM.

Two years later, he was back at Warner Bros, directing Merrie Melodies cartoons, continuing to do so even after WB technically closed down their animation studio in 1963. Only in 1967, when WB officially ended all of the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons, did Freleng finally stop producing Merrie Melodies cartoons, moving on to the Pink Panther and various animated television specials.

In a rather vicious twist, financial setbacks forced Freleng to sell off the few assets he had not owned by Warner Bros or MGM to Marvel in 1981, who in turn sold those assets to Disney in 2009 as part of their takeover of Marvel Entertainment. It was almost as if Freleng had never left the company. That is, if you ignore all of his major work at Warner Bros.

Back in the early 1940s, of course, no one could or did imagine what Disney would grow into, much less Bob Iger’s later policy of “Buy all the things.” Walt Disney was running an animation studio that, if highly admired for its artistry and technique, was beset by unhappy, often striking artists, along with ongoing financial troubles, thanks to Walt Disney’s insistence on lavishly spending money he often did not exactly have on both new studio space and intricate, detailed animation that no one over at WB could even dream of. Including a little film called Fantasia (1940) which had cost a then-unheard of sum of money and time for an animated feature and promptly bombed at the box office. Freleng figured he could take the time to poke a little fun at his former employer, as long as he kept the cartoon entertaining.

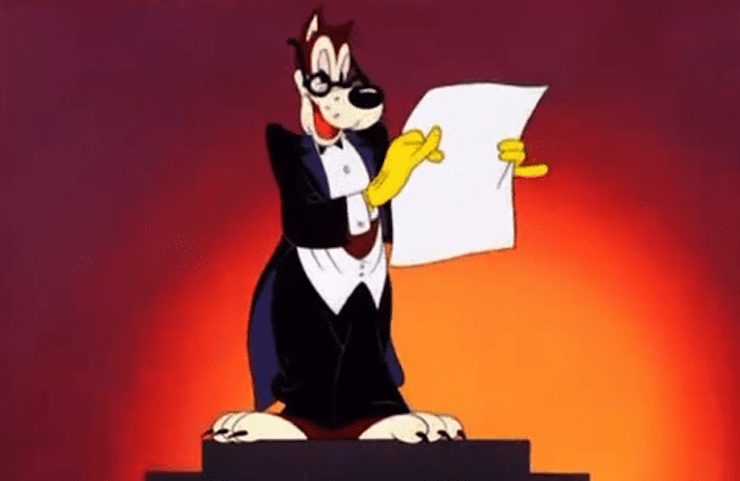

The result, the 1943 Pigs in a Polka, part of the Merrie Melodies line, was not exactly subtle in its attack, opening as it does, with a scene deliberately recalling the ponderous introductions done by Deems Taylor for all of the Fantasia segments. Mel Blanc—er, that is, the Big Bad Wolf—stands on a similar podium, with similar lighting, and like Taylor is dressed in a formal tuxedo, though honesty compels me to admit that the Big Bad Wolf is not exactly rocking the tuxedo look here. He almost manages to look, well, unkempt—possibly because he has chosen not to wear shoes with this fine outfit, or possibly because he is wearing yellow gloves that just don’t match the rest of the outfit, or possibly because bits of his fur are popping out of the tuxedo, or possibly—don’t hate me here—because he’s a wolf, and wolves are just not good at fashion or choosing well-fitting tuxedos. As a final intellectual touch, the wolf wears glasses, just as Taylor did in the film.

Mel Blanc—er, that is, the Big Bad Wolf—then ponderously introduces, in much the same way Deems Taylor had introduced the Fantasia segments, except with more pronunciation errors and in Mel Blanc’s more distinctive tones, the tale of the Big Bad Wolf and the Three Little Pigs, set to the Hungarian Dances by Johannes Brahms. A highly condensed and edited version of Hungarian Dances that I suspect left the ghost of Johannes Brahms desperately wishing that ghosts have the ability to hire lawyers and sue Hollywood studios, but I digress. And to be fair, the same thing could be said—and was said—about all of the musical selections for Fantasia.

Introduction over, the rest of the cartoon shifts into what is on the surface a retelling of the fairy tale of the Three Little Pigs except with a lot more dancing and costume changes and a record player, but what is really an opportunity for the WB animators to parody Disney’s Three Little Pigs and various aspects of Fantasia—most notably the massively criticized Pastoral Symphony segment and the more popular Dance of the Hours segment. The three pigs—helpfully wearing shirts that label them as Pigs 1, 2, and 3—don’t just use the same pipe and fiddle used by the Disney pigs, but are deliberately modeled after the cute little cupids in the Pastoral Symphony section, even striking some similar poses. The Big Bad Wolf not only dons various disguises, as did the Disney wolf, but is modelled after the alligator in the Dance of the Hours segment.

It’s amusing, if you’ve seen Fantasia. If you haven’t—well, the cartoon does contain several other gags, including the one where a watching bird waits for Pig 3 to build a nice brick wall and then comes and puts a straw nest right on top of it, because, bird. And the one where Pig 1 and Pig 2 seem to be falling for the Big Bad Wolf’s seductive dance—only to dart out wearing evil expressions, his costume and, uh, his tambourine, which has somehow turned into two tambourines, and the one revealing that the Big Bad Wolf has somehow or other been balancing a record player on his butt while playing the violin, like, this sort of dedication to a role demands respect. Yes, yes, I know he’s only going to these lengths and using this awkward angle in order to kill the little pigs, but, respect, Wolf, respect.

The cartoon has other minor delights—the way Pigs 1 and 2 manage to twirl themselves into actual knots watching the Big Bad Wolf dance around them, or the way the sticks used by the second pig to build his house are actually matches—allowing the Wolf to use the matches on the straw house later, burning it down instead of blowing it down. Or the way the pigs hand the wolf some mouthwash. Or the way the cartoon and its characters are cleverly, perfectly matched to the music. Oh, the cartoon has the usual Looney Tones/Merrie Melodies incomprehensible moments—I would really like to know why such a small brick house needs an elevator, for instance, although since it’s mocking a cartoon where a pig was playing a piano made of bricks, I suppose I shouldn’t complain all that much. It’s a parody.

And one that’s readily available nearly everywhere, thanks to United Artists’ failure to renew its copyright on time. You can find it in a number of WB cartoon collections and on YouTube and Vimeo.

Parents should, however, be cautioned that the cartoon uses some stereotyped imagery associated with gypsies, presumably because of the “Hungarian” part of the Hungarian Dances, or because the Disney cartoon had also featured the Wolf dressing in stereotyped costume.

Its very existence must have been at least somewhat galling to Walt Disney, who had pioneered the musical cartoon genre with the various Silly Symphony cartoons, but who at this point was not just still losing money on Fantasia hand over fist, but stuck making war cartoons and the deeply weird The Three Caballeros (1944), none of which were exactly projects of his heart.

The next short at least didn’t spend quite as much time mocking beloved Disney projects—though it, too, had a Disney connection, if one that can kindly be called a bit of a stretch. This was the 1949 The Windblown Hare, starring no less of a personage than the great Bugs Bunny himself. The connection? Two of the designers of Bugs Bunny, Charlie Thorson and Bob Givens, had both trained at the Disney animation studios before heading to Warner Bros; Clark Gable, one of the many inspirations for Bugs Bunny, had sung “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf,” from the earlier Disney cartoon, in It Happened One Night (1934).

The Windblown Hare opens on the three little pigs reading their own story, which I must say is a clever way to avoid problems. They immediately realize that they need to dump their straw and stick houses before the wolf arrives—and fortunately find a sucker almost immediately: Bugs Bunny. This is an earlier, rougher, Bugs Bunny, one who is delighted to fork over $10 for a straw house, since he wants something more than his hole. It’s a not particularly veiled reference to a relatively common practice then and now—trapping unsuspecting buyers into paying far more than a property is worth—and ridding the seller of a major problem.

Unfortunately for Bugs, the Big Bad Wolf is also reading the story, anxiously practicing his lines, convinced that he has to follow it, because, well, it’s in the book. He blows down first the straw house, and then the stick house, in both cases, crushed to discover that they do not have any pigs. What they do have is a Bugs Bunny, announcing: “Of course, you know, THIS MEANS WAR.”

War, the way Bugs Bunny does it, involves disguising himself as Little Red Riding Hood and forcing the Wolf to try to catch up to that part of the story. Fortunately, in true Looney Tunes fashion, a convenient sign pointing to a SHORTCUT TO GRANDMA’S HOUSE appears just in time—though the Wolf is running so late that the doesn’t have time to eat an indignant Grandma.

It does not take Bugs and Wolf too long to admit that they are not, actually, Grandma and Little Red Riding Hood, although they do need a bit of classic Looney Tunes chasing before they can finally get down to grievances and realize who the true culprits here are: the pigs. And off they head to the brick house—with a bit of dynamite.

This is not, it must be said, one of the all-time great Bugs Bunny cartoons, or even a second rate Bugs Bunny cartoon, which might explain why although Warner Bros records show that The Windblown Hare was put into production and completed in 1947, it was not released for a couple of years. But like most of the Bugs Bunny cartoons, it’s at least amusing, and I do like the twist of all of the characters interacting with their own story—and deciding that yeah, no, they are going to go with their own plot. Not to mention a version which does not show the first two pigs as lazy fools who deserve their fate, who are only saved by a grumpy if cleverer pig.

But WB saved the best of their Three Little Pigs cartoons for last: The Three Little Bops (1957), released under the Looney Tunes label. Like Pigs in a Polka, it was directed by Friz Freleng, and largely animated by Gerry Chiniquy and Bob Matz. And it just may be one of Freleng’s masterpieces.

Like that earlier cartoon, The Three Little Bops centers on a musical number. But this time, instead of a classical piece, Freleng built the cartoon on an original song, the jazzy, west coast swing “The Three Little Bops.” The song, melody and lyrics, is credited to jazz musician and trumpeter Shorty Rogers, who would go on from here to compose music for various films and arrange songs for the Monkees. Friz Freleng, however, took credit for the script in later interviews, and since the entire cartoon is sung-through, it’s entirely possible that Freleng wrote the lyrics to a melody and arrangement by Shorty Rogers. Considerable confusion also remains over who, exactly, is playing which instrument at any given time, although Shorty Rogers presumably did all of the trumpet bits, and Friz Freleng apparently sung pretty much the entire cartoon.

That makes this, incidentally, the only WB cartoon of the period to not feature the voice of Mel Blanc at least once. I have no idea why—perhaps Mel Blanc was busy recording elsewhere when Freleng and the other musicians recorded the song, or perhaps he just didn’t want to sing. Regardless, Freleng’s choice to sing and direct a cartoon that has no other dialogue except for the song—a song he may have partly written—makes this arguably one of the ultimate Freleng cartoons, if not the ultimate one.

Enough about the credits. The cartoon starts by telling us to “Remember the story of the three little pigs. One played a pipe and the others danced jigs,” immediately contradicting not just the original folktale but all of the earlier pig cartoons, but let us move on. The pigs, we are told, are still around, but now playing music with a modern sound. Which means, it seems, giving up the flute and fiddle for saxophone, drums, guitar, double bass and piano. The drummer pig looks particularly ecstatic throughout almost the entire cartoon, except when he has to switch instruments or throw a wolf out of a dance club, but I anticipate.

Anyway, the pigs are playing, the humans are dancing, and the wolf, impressed with the pigs’ musical talent, announces he’s joining their band. Alas, even in the gifted hands of Shorty Rogers, the wolf is, well, just awful. The pigs toss him out of the club, infuriating the wolf: “They stopped me before I could go to town—so I’ll huff and puff and blow their house down!”

The pigs, unmoved, find another place to play—”The Dew Drop Inn, the house of sticks, the three little pigs were giving out licks!” and look, you know, this is theoretically a kids-friendly cartoon, so I’m just going to leave that there, right along with the Liberace comment, though if you want to read or sing something into this, go right ahead. The wolf, not worried about the implications of the lyrics or Liberace, tries to join the band again. It fails. The wolf blows down this venue too. The pigs conclude, “So we won’t be bothered by his windy tricks, the next place we play must be made of bricks!”

That leaves the wolf with only one recourse: disguises. A recourse that might have worked better had he not, apparently, received his Disguise Training from Wile E. Coyote—the products he uses may not come from Acme, but they have more or less the same results.

On the other hand, once in hell, the Big Bad Wolf finally—finally—learns how to play the trumpet, teaching the pigs—and us—an important lesson about morals and music:

“The Big Bad Wolf, he learned the rule—you gotta get hot to play real cool!”

There’s so much to be said about this cartoon, from its clever incorporation of the original “huff and puff” lines from the original story to this, to its frequently clever lyrics (I’ve left most of the best of them out), to the hilarious disguise sequences, to the sheer joy on the faces of all three pigs, to the way even tiny moments are perfectly syncopated to the ongoing beat, to the indignant square drawn by one of the pigs to describe the wolf, to the way that the wolf tries to join in a jazz/swing music session by… opening music, a complete no-no for jazz groups at the time, to the clever ending.

It helps, too, that pretty much every character in the cartoon is highly sympathetic—the pigs just want to be able to play their gigs in peace, the wolf just wants to play the trumpet, and the humans just want to dance—meaning that the happy ending is satisfying for everyone.

Oh, certainly, I’ve seen an interpretation of the cartoon that reads it as a less happy commentary on white musicians taking over black jazz. And I gotta admit, the moral message here—wanna join a band? Then be evil enough to get sent to hell!—is perhaps not exactly the message most parents want given to their small children. Morality aside, however, I’d still rate this as one of the most entertaining of the classic WB cartoons, and my hands down favorite retelling of the Three Little Pigs, ever.

Audiences did not immediately agree—possibly because the short doesn’t feature any of the well-known WB cartoon characters or Mel Blanc. The song, however, began to be covered by other jazz musicians and artists, gaining popularity in its own right, and reinvigorating interest in the cartoon. Warner Bros eventually included it in their list of the 100 greatest Looney Tunes/Merrie Melody cartoons, which meant various releases on DVD/Blu-ray collections.

That—and Warner Bros’ success at renewing the copyright for this cartoon short on time—also means that this short is considerably harder to track down, but it’s available at both Amazon and iTunes streaming as part of Looney Tunes All Stars, bundled together with yet another cartoon short featuring the Big Bad Wolf—this one the less successful The Trial of Mr. Wolf, that is, the Big Bad Wolf of “Little Red Riding Hood, not Pigs in a Polka or any of the other Three Pigs cartoons, despite looking and sounding suspiciously familiar to all of them and despite having a compass that would allow him to find the homes of the Three Little Pigs. Suspicious. In any case, you can watch both cartoons, or just fast forward to The Three Little Bops, and have a much better time, or just hope that it pops up on Cartoon Network at some point. In any case, if you have any fondness for animation, or pigs, or swing music, I’d recommend giving it a try.

In the meantime, with four posts dedicated to this fairy tale, I think it’s time to say “Thaaatttt’ssss allllllll fffffffffffffooooooooooolllllllllllkkkks!”

(What? I’ve always wanted to end a post that way.)

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.